In 1915, while driving along England’s south coast, the entrepreneur Charles Neville had an idea. Once the war was over, his fellow countrymen - fighting in the trenches just a short distance away across the Channel - would surely want a stake in the green and pleasant land they were so desperate to preserve, something better than the urban slums many had left behind. The expanse of beautiful but desolate cliff-top coastline before him, just six miles east of the resort town of Brighton, seemed perfect for Neville’s vision of a seaside arcadia.

His resolve hardened when the British Government began their campaign of ’Homes fit for Heroes’ for returning servicemen. Neville thus acquired over 600 acres of Downland on the Sussex coast for just £15 per acre. Then, at the beginning of 1916, he launched a competition in the Daily Express to name the development.

‘New Anzac-on-Sea’ was chosen as the winner, and many of the streets were destined to be named after early First World War battles: Marne, Mons, Loos and Ypres Avenues among them. But, following the tragic events of Gallipoli, Anzac was changed to Peacehaven, and the streets to popular female names of the day.

Neville believed Peacehaven would be the perfect place to recover from the traumatic effects of the war. The idyllic setting, sea air and simple lifestyle he planned would be an aid good health and recuperation. He made the plots relatively cheap and, as a result, working-class families wishing to escape from sprawling industrial cities or anonymous new suburbs started to purchase plots and gradually build makeshift homes. Suffice to say, many of the new inhabitants had just returned from the trenches.

*

During the First World War the concept of ‘shell shock’ was ill-defined. Cases were interpreted as either a physical or psychological injury or, in less liberal minds, a simple lack of moral fibre. Yet, despite these disagreements, and the fact that the term is no longer used in military discourse, shell shock has entered into popular imagination, and is often identified as the signature injury of the First World War.

By December 1914, 10% of British officers and 4% of enlisted men were suffering from "nervous and mental shock", but following the Battle of the Somme in 1916, 40% of casualties were considered shell-shocked, resulting in concern about an epidemic of psychiatric disorders, which would be costly in both military and financial terms.

At the end of the conflict, Sir Philip Gibbs, one of five official British reporters during the First World War, wrote: “Something was wrong. They put on civilian clothes again and looked to their mothers and wives very much like the young men who had gone to business in the peaceful days before August 1914. But they had not come back the same men. Something had altered in them. They were subject to sudden moods, and queer tempers, fits of profound depression alternating with a restless desire for pleasure”. Combat veterans often reported symptoms including headaches, extreme anxiety, flashbacks and sensitivity to loud noise. There was no consensus about how to treat the condition.

Ten years after the end of the First World War there were still 65,000 veterans receiving treatment for shellshock in Britain, although by then the term had been superceeded by ‘postconcussional syndrome’, then ‘combat stress reaction’ and finally ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ (PTSD) as we know it today.

*

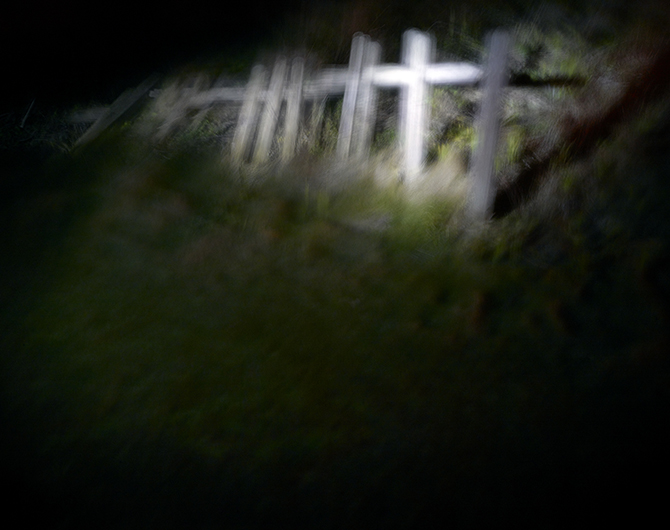

For this work, a commission from Bruges Museum in Belgium, I tried to imagine myself as a veteran coming to live in Peacehaven after the war. My aim (using long, handheld exposures, powerful torches, electronic flash and even the occasional smoke machine) was to create an atmosphere of unease and terror amongst the sleepy bungalows of the town, where a fleeting glimpse or an unexpected sound might spark nightmarish memories of a life best forgotten.